A BUTTERFLY DREAM

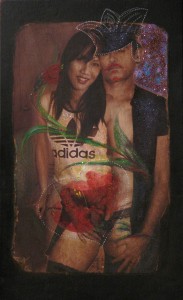

Can porn be innocent? Or sexual desire in general? And why do perverts dream of flowers? These are some of the questions that one encounters in Samvel Saghatelyan’s 2010-13 series Transromance. Each of the eleven mixed media ‘tableaux’ that make up the series, feature the artist clad in sadomasochistic leather gear and stockings, accompanied by a transgender person. The photographic image of this couple is printed, photocopied, collaged, drawn over by hand, pasted onto a cheap cardboard and then rubbed over for a patina effect.

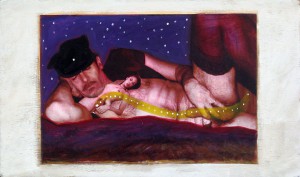

The sequence unfolds like a dream. The trans woman initially appears as a projection rising from the artist’s slumbering body. She then materialises as a more concrete being, posing alongside Saghatelyan as if in a family photo and finally helping him reach a firework-like climax. It’s a quasi-biblical narrative (which at one point takes place on the foot of Mount Ararat) seen through the unashamedly pornographic prism of phalocentric male narcissism. But the narrative here is problematised by its representation. Awkward and cartoonish, the childish execution undermines the troubling nature of sexuality which lies at the core of Transromance. Aggression dissipates under the layers of genteel flowers, rainbows, mountains, purple glitter and hearts. Taken as a whole, Transromance appears like pages from a middle-aged man’s wet dream in the form of a teenage girl’s personal diary.

This bawdy tone is typical of Saghatelyan’s practice since the mid 1990s and has become more prominent since his move to Los Angeles in 2002. One of the works from the 1996-2013 series Body, for example, depicts ghost-like phalluses rising out of the windows and doors of the Ejmiatsin Cathedral – the holiest of Armenian religious sites. Such brazen attacks on institutionalised value systems are representative of an artist who emerged during the period of Armenia’s transition from a Soviet to an independent state between 1988 and 1991

Chief amongst the many things placed on the operating table in Transromance is male sexuality and desire. Its grotesque space of power and domination is lampooned as a kitsch, masturbatory act. Literally so in two of the last images, where the male figure, named ‘Armenian King’ urinates and then jerks off over his submissive fantasy mistress. However, despite their open sarcasm, Saghatelyan’s images rethink the post-modernist arsenal of pastiche and parody. The artist complicates the use of such devices through the emotive, tender tone that floods the works. ‘I was thinking of Sayat-Nova while working on the series. It related to the kind of trance-like state where the simultaneous presence of the opposites creates a vague space of in-betweenness in which sexuality, images, feelings and perception are all ‘trans’.’(1)

The reference to the 18th century Armenian bard Sayat-Nova is telling as Transromance clearly gestures towards Sergey Paradjanov’s 1969 film Colour of the Pomegranates. In the film, the poet was played by an actress (Sofiko Tchaureli) who also personified his love interest and muse. This duality is shared by Saghatelyan’s hero. The trans-woman and the male figure are clearly a part of the same body, shown at times like Siamese twins.

Their liaison is further complicated as the transgender character is represented by different persons of South-East Asian origin. In this ambiguous body of desire, sexuality is made fluid and paradoxical. Hyper-masculinity, hyper-femininity as well as ethnic stereotypes can be provocatively indulged in, because ultimately they are shown to be nothing more than ridiculously sentimental and co-dependent garbs. Like in a 19th century photography studio, the fun lies in the exchange and the performance during which new poetics of identity can be developed. This aspect is yet again reinforced by the aesthetic of the works where the compositions are constantly repeated and only their painted surfaces change, like skins or costumes. What the artist seeks in this liminal, transitory condition is the possibility for guiltless enjoyment and exploration.

Transromance is symptomatic of the kind of contemporary art, exemplified by international artists such as Catherine Opie, Jeff Koons and Patt Brassington, that has digested the lessons of psychoanalysis, post-structuralism and queer theory to go beyond critique. With impressive effortlessness, the series weaves through these terrains to reach back to a point of pleasure and emotion. As theorist Judith Butler has noted ‘to operate within the matrix of power is not the same as to replicate uncritically relations of domination.’ (2) It is this ‘knowingness’ that allows Saghatelyan to fearlessly play with problematic symbols, clichés and meta-narratives.

What we see in Transromance is a self-aware theatre of appearances in which art, body and desire shift-shape and morph by assuming a variety of interchangeable masks. By synthesising the aesthetics of family photographs, folk and naïf art, Saghatelyan makes evident the nature of images, identity and gender as a socio-cultural construct. But rather than negate these confines, Saghatelyan unfolds his game within them normalising and domesticating that which is repressed and derided. Rather than being merely clever, the images acquire their strength on the basis of their honesty. Recalling critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the ‘carnivalesque’ (3), Transromance utilises humour, confession and burlesque to create a productive space in which homogeneity, power and ideology are dissolved to give way to the romance of transformation.

Transromance was presented as a one day happening-event, which took place at the private apartment of film historian Shahane Yuzbachyan in Yerevan, Armenia on September 12, 2013. The show was organised with the assistance of ‘Lusadaran’ Armenian Photography Foundation.

Vigen Galstyan

curator, 2013

i) Conversation with the artist, Yerevan, 09.09.2013

ii) Judith Butler, Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity, Routledge, New York, London, 1990, p 40

iii) See Mikhail Bakhtin, Rebelais and his world (1940), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2009

This essay originally appeared in the booklet accompanying the exhibition.