Like a sponge, photographs suck in secrets with the passage of time. They lose their owners, become displaced, worn and damaged. Names and information associated with their making and their contents is often lost within only a few decades of creation. With time, photographs become objects of mystery despite their nature to be anything but that.

Lusadaran has many such photographs, but one of our recent acquisitions is a particularly delightful example of a 19th century photographic ‘whodunit’.

It is a traditional cabinet portrait from the turn of the 20th century, probably made between 1895 and 1905. This is indicated not only by the subject’s clothes, but also the printing medium. An early form of gelatin silver paper was used for the print, common during this transitional period when photographers were switching from making albumen prints to using the more practical gelatin silver process.

The portrait is of a woman in her 30s, wearing a fashionable, albeit restrained Western dress, sitting cross-legged next to a coffee table with a tar (an ancient string instrument popular in Iran and the Caucasus) perched on her knee, ready to play. The photograph has reached us in quite a damaged state. At one period someone had visibly tried to destroy it as it has been broken in half in the middle. It was then glued back together with a large piece of paper. There were no visible inscriptions that would give us a clue as to the identity of the woman or the photographer.

19th century studio portraits rarely feature women holding anything other than babies or the hands of their husbands. Sometimes a woman or a young girl will appear with a certain prop found in the photographer’s atelier – a bicycle or more likely a book. In genre scenes, particularly those made to represent the ‘Orient’, women are often seen with household utensils, holding wine jars, hookahs or mirrors – objects of pleasure that signal their own status as objects pleasuring the predominantly male clientele of such images. Thus, it is quite unusual to see a photograph of a woman with an item that represents something other than her domestic status as daughter, wife or mother.

Hence this photograph immediately stands out from countless others since it features the woman with an object that stresses her status as a professional musician. Considering the fact that the photograph was made in the Caucasus at the end of the 19th century, this makes the image even more remarkable. Very few images of professional women living and working in the Caucasus in the 19th century have survived.

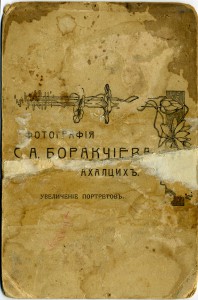

S. A. Borakchiev. Portrait of a woman with tar. Verso of the cabinet portrait after the removal of glued paper.

The back of a cabinet photograph often carries photographer’s studio stamp and its location. Hoping to find this information, it was decided to carefully remove the white piece of paper glued on the back of the card. The photographer’s backstamp appeared almost immediately. It is in Russian and says ‘Fotografiya S. A. Borakchieva / Akhaltsikh / Uvelechenie portretov’ [S. A. Borakchiev’s photography/ Akhaltsikh / Portrait enlargements].

The name of the photographer was unknown to us and it was the first time we had come across portraits from this studio. After searching on the Internet we were able to locate two more images from Borakchiev, held in the National Library of Georgia. Akhaltsikh (Akhaltskha in Armenian), where the studio was located, was predominantly an Armenian-populated city in Georgia’s southeast, close to the Turkish border. It had quite an affluent community famous for its production of jewelry and hand-woven lace. Akhaltsikh was also a major center of Armenian culture. It had a number of schools and colleges and was one of the first cities to have a permanent Armenian theatre, established in 1860. The city also attracted numerous musicians practicing traditional music. Many of the bards, such as Havasi, who lived and performed in Akhaltsikh have in time become icons of traditional music in Armenia and the Caucasus.

There were numerous photography studios in Akhaltsikh since at least the late 1860s. Practically all were run by Armenians and like jewelry making, photography was considered a family business, being passed from one generation to the next. Whether Borakchiev was an Armenian or not is not entirely clear. The surname stems from the Turkish word ‘börek’, which stands for a type of pastry made from thin, flaky dough. Hence, ‘Börak-chi’ means ‘börek-maker’ or simply, baker. The surname was russified with the addition of the suffix ‘iev’ – a popular trend amidst the photographers of the Caucasus trying to attract a multi-ethnic clientele.

It was customary amidst the Armenians, particularly those from the Ottoman Empire to adopt surnames from Turkish descriptions of their profession and append the Armenian suffix ‘yan’. Many are still in use today. Nevertheless, searching for the surname ‘Borakchiev’ did not produce significant results. It does not figure either in Armenian, Turkish or Azerbaijani surnames currently in use. While it is possible that our photographer was of Turkish or Azeri origin, it would be highly unlikely. There are very known Turkish photographers in the 19th century and not a single Azerbaijani one since the profession was generally frowned upon by the Muslim population well into the 1920s. Regardless of the photographer’s puzzling background, his name and place of activity give us an insight into the richly multicultural milieu of the Caucasus in which various ethnic traditions mingled and influenced each other to produce a truly unique cultural landscape.

But what of the woman? Obviously from a middle class family, her facial features are quite

clearly Armenian. Her upright pose and forceful gaze hint at a personality that is strong and independent. There is a certain sense of pride with which she wields this instrument. The tar was a favorite amidst Armenian and Azerbaijani bards but women did not generally play it in the 19th century, unlike the ‘Qanun’ for example (a type of Middle Eastern zither). However, numerous depictions of women playing the tar can be found in Persian art and literature and the practice seemed to have existed in Armenia as well, albeit kept in the private domain of the house. Indeed, very little research has been done on women who might have performed music publicly in the Caucasus in the 19th century. Although the theatre stage was replete with actresses and singers, we don’t know of many female musicians as such, let alone ones that played traditional instruments.

With her slightly disheveled hair, pocket watch, stern European clothing and make-up free face, the ‘tar player’ of our photograph is unquestionably an emancipated individual who is (consciously or not) making a stand against traditional representations of women. She is fully in control of her image – presenting herself as both a modern creature in step with the times and someone who embraces her cultural legacy as an essential part of her identity. We don’t know whether she performed publicly. But as it sat on a mantelpiece or in a family album, this photograph afforded her, like so many other women in the 19th century, an opportunity to express her individuality for others to see.

The back of the photograph holds one more fascinating puzzle piece. A barely legible word in Armenian, handwritten in red ink seems to spell ‘Mozart’. It was perhaps inscribed in recognition of this unknown woman’s talent whose only trace remains embalmed in this tantalizing photograph.

Vigen Galstyan, 2015