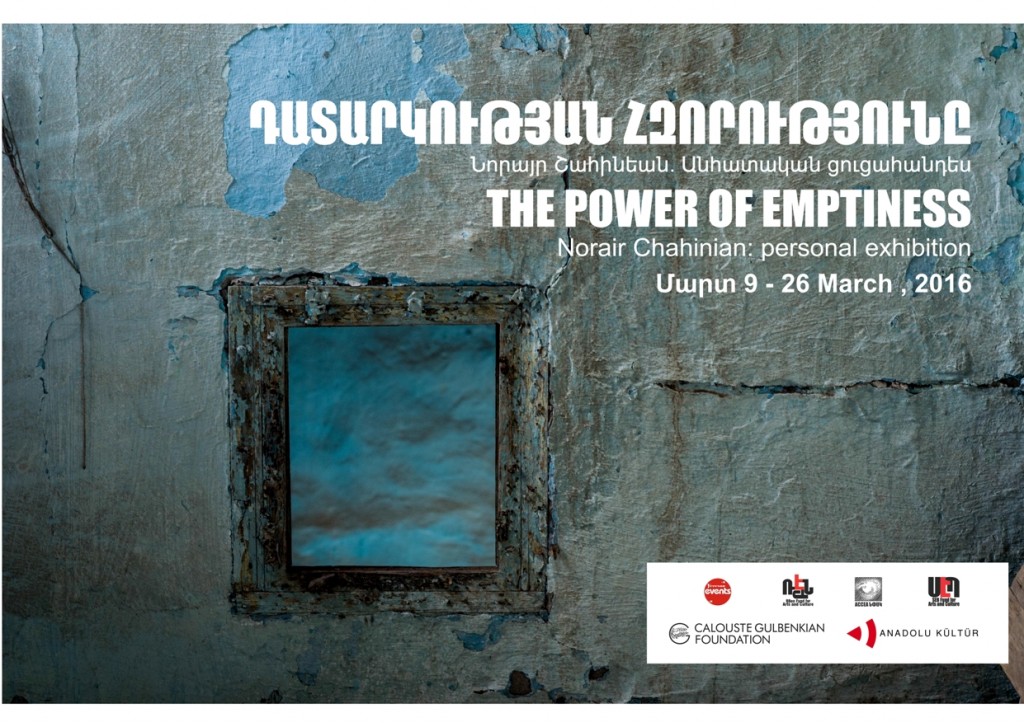

The Power of Emptiness

March 9, 2016 – March 26, 2016

The Power of Emptiness

Norair Chahinian

(Official press release)

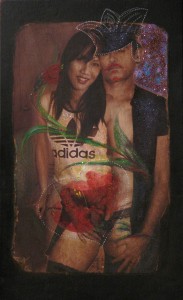

The photographs taken in Turkey by Sao Paulo (Brazil) born photographer Norair Chahinian strike viewers in a number of different ways.

First through their witnessing of life in various regions of Anatolia ‘from the outside’, by someone who has come all the way from across the world, thousands of kilometers afar. But more importantly, through their depiction ‘from within’ of the return of an Armenian to his roots in Maraş, Urfa, İskenderun, as he visits the land of his family after a gigantic lapse of one hundred years.

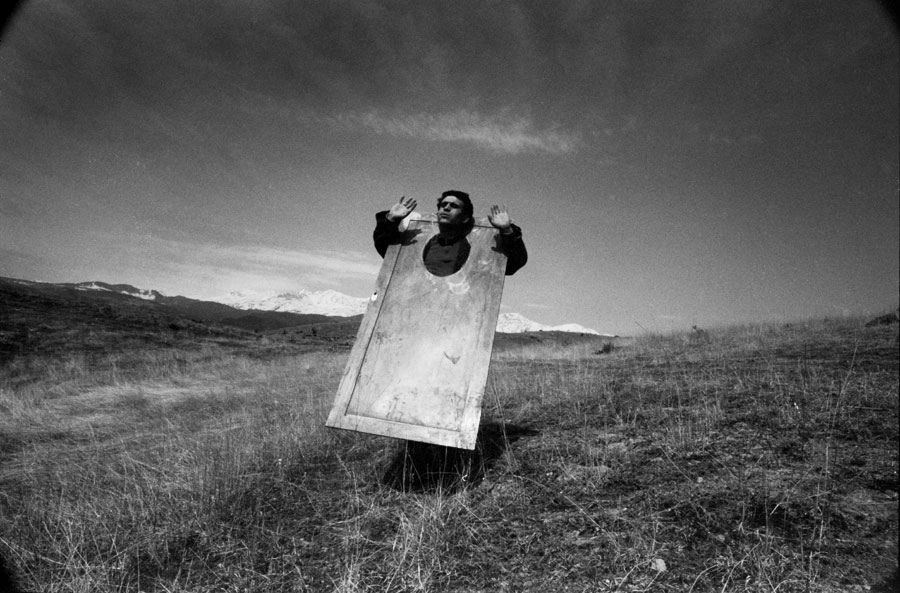

“The Power of Emptiness” is an attempt to come to terms with the potentials and the impossibilities embodied at the heart of this return, this witnessing.

It is the story of a fourth-generation Armenian forcefully torn apart and banished from his lands showing the courage to look the past, present and future straight in the eye.

Norair Chahinian was born in Brazil as the child of a family that had fallen victim to the Committee of Union and Progress’ genocidal politics against Armenians during the final era of the Ottoman Empire.

His grandmothers and grandfathers had lost their families during those days of catastrophe, took refuge in Aleppo, Syria, under dire circumstances and had migrated to Brazil, South America from there, sharing the fate of Armenians who like themselves were dispersed to all corners of the world.

Chahinian was raised in an Armenian diaspora community and internalized all elements of this identity. Norair Chahinian, who knew his family history thoroughly, learned Armenian and believed that the recognition of the Armenian Genocide is not a matter of retribution but of justice, was familiar with Turkey and Turks through a narrative weaved with deaths and violence.

He experienced a turning point in his life the moment he decided to expand this narrative by personally coming into contact with Turks living today and the lands that once belonged to his own family. The photographs in “The Power of Emptiness” present us with the observations Chahinian made precisely at this turning point.

This quest brought the photographer to Turkey where he knew no one, did not speak the language; where he was familiar neither with the climate nor the ways of the people. But in no way as a tourist.

He came here determined to build a bridge between the past and present, as the last link of a family who was the victim and witness of the catastrophe experienced one hundred years ago but had managed to live, survive and build a new life on the other side of the ocean.

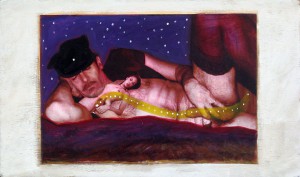

Ensuing from this past and determination, there is absence and emptiness as well as life and the perpetuity of living in the photographs Chahinian took in different cities of Turkey. The emptiness that remains from those who died, who were forced into exile and the power of this emptiness is undeniably reflected in each and every frame.

The rainbow over the derelict churches, children playing on deserted streets, slogans of the military coup era written across Armenian epigraphs, an aggrieved suitcase in an empty home waiting as though it was left there only yesterday. The power of emptiness, the emptiness of power…

These photographs, which were taken by a person rendered homeless and rootless; depicting the journey towards a land where his source lies in order to fully establish his coordinates on earth and to take roots again, also express a universal quest.

In going back to his roots, and towards the local, Chahinian treads on a more worldly ground and becomes universal.

Rober Koptaş