Photography was the most pervasive media of the 20th century and it continues to be so in this new one as well. Sifting the internet for interesting, relevant and the trully remarkable can be a monumental task – drowning as it is with countless websites on the subject. Starting a blog on the subject within Lusadaran’s website seemed an inevitability as it gives us an opportunity to respond with more immediacy that the online environment demands. So here is our first post and what better way to kick-start than a look at the 2012 World Press Photo awards.

Samuel Aranda. WPP 1st prize for 2012

The award, which has been given to the most remarkable news photographs since 1955 by the independent foundation based in Amsterdam has been seen as something of a beacon for photojournalism. Museums and curators often scoff at its populist drive, but its success with people all around the world is unquestionable. It would be understatement to say that any news photographer worth his salt quests after the main award. Not only is it the most prestigeous of its kind but above and beyond everything it offers an instant celebrity status for the photographer and the kind of publicity that money could never buy. This is particularly vital in the age of the digital, as it becomes harder and harder to make a buck by being a professional photographer (too many people are doing it you see).

As a voice of authority WPP award often stands for quality. It validates the truth and the power of the chosen images in the eyes of the public, conditioning in part the way we learn to read and asses images we see in the news. Needless to say that this is problematic in too many ways. The lack of a critical forum and the entire competitive framework create a compromising context for these photographs.

The competition always boasts at least some remarkable photographs, but in recent years the line-up of winners has exposed a formulaic preset according to which images are accorded their awards. A lot has been written about this year’s winner – a photograph by the Spanish photographer Samuel Aranda taken for the New York Times. This image of an Islamic woman, fully clad in a burka and embracing her wounded son has raised the ire of critics and bloggers all over the town.

Aranda seems to have captured ‘the decisive moment’ (both visually and thematically, as the photograph is meant to represent the Arab Spring uprising in Yemen) yet it is as far removed from the Bressonian notion as a photograph could ever be. Its overtly universalist appeal is so obvious as to be practically poster-like. For Cartier-Bresson, the moment always resided in a wider context through which we could recognise the importance, indeed the singularity of the chosen second. Instead Aranda dispenses with all but a painterly void, presenting his monumental subjects outside of time or… it seems place. Despite what the caption tells us (not a lot), we can not perceive these two figures as anything but ciphers.

Paolo Woods. Radio Haiti. 3rd prize in Daily Life category

The metaphorical and literal transposition of ‘Pieta’ composition upon the non-Christian subject smacks as a particularly off-handed attempt at taming the ‘other’. To this writer, this appears like a thinly vailed reboot of an Orientalist fantasy, a kind of Western taxonomy of pain and suffering conjured for our pleasure. Yes, I meant pleasure. For when we look at this photograph we can see nothing but a reflection of our own real or projected pain. The image acts as a catharsis for our own emotions rather than disclosing anything about its ghostly, literally faceless subjects who remain entirely anonymous and merely functional. Susan Sontag would turn in her grave.

Compare this to a photograph by the Dutch photographer Paolo Woods called Radio Haiti, which has rather ridiculously garnered only the 3rd place in the ‘Daily life’ category. A simple, but striking composition holds its subject at a respectable distance, yet gives her an incredible presence and focus, carefully framing her within a window of things that make up her world. It’s a remarkable photograph through which SO MUCH can be garnered on both intellectual and emotional fronts.

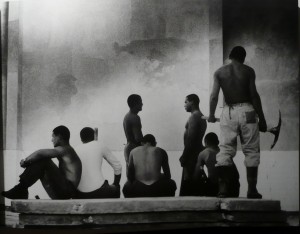

Ray McManus. Scrum Half. 2nd prize in Sports category

The modernist or rather classicist tendencies of Aranda’s photograph are much more

presciently and rightfully employed by the sports photographer Ray McManus. His image of rugby players during a moment of intense battle is both unashamedly romantic and achingly beautiful. Its sense of movement, texture and sensuality of bodies in action would do Delacroix proud. It is not particularly important who the rugby players are – their conflict is completely controled, staged and timeless – the focus here is the game itself with its peculiar ballet of masculinity.

Whatever… at the end of the day, WPP demonstrates yet again that it is painfully behind the enormous leaps and advances that photography has made within the last forty years. Illustration still rules the day.

VG