The studio name ‘Photogr. Artistique G. Lekegian & Co’ appears on some of the most famous images taken at the end of the 19th century in Egypt. For nearly three decades, until the 1910s, the Lekegian studio held an exceptionally prominent position in Cairo producing thousands of images depicting the everyday life, nature and architecture of Egypt. Yet, despite his fame, Lekegian was quickly forgotten in the years that followed and very little biographical detail has surfaced about the man behind this exceptional legacy.

Lekegian, whose first name is mentioned as Gabriel in some secondary sources, was born in the Ottoman Empire, possibly at the end of the 1850s. His initial appearance on the public arena occurred as an artist. By 1880, Lekegian is based in Constantinople and is the student of the noted Italian expatriate artist Salvatore Valeri (who later married Lekegian’s sister, Maria)[1]. Working in watercolours, Lekegian produced a series of figurative and genre studies in the exquisitely detailed style of his teacher. Although blatantly academic in style, Lekegian’s delicate works were infused with a desire to record the people and life of the Ottoman Empire with more objectivity. Despite the presence of Orientalist tendencies borrowed from Valeri and Gerome, the propensity towards realism is already palpable. These watercolours, few of which have begun to resurface recently in auctions around the world, were initially exhibited in Istanbul in 1881 and also, later in 1885 in London.

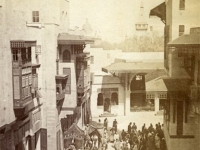

It is not know what promoted Lekegian’s sudden move to Cairo or the exact date of his arrival there. Neither are there any details about how his switch to photography occurred. Considering the exceptional quality of his early works, it is likely that he had apprenticed in one of the Armenian or Greek photographic studios prior to embarking on a career of his own. Perhaps, recognising the promising commercial prospects of photography in such an international magnet, as was Egypt at the time, Lekegian made the decision to leave the already competitive scene in the Ottoman Empire. He was, as evidence suggests, an adroit businessman. After quickly establishing his studio opposite the Shepherd’s Hotel at the heart of Cairo’s European district, Lekegian positioned himself as an ‘artistic’ photographer, signalling himself and his work as aesthetically superior to his mainly French or Greek competitors.

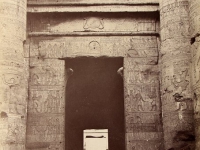

The studio immediately began to produce quantities of beautifully composed photographs that were popular with tourists and European residents of Cairo. Among the depictions of famous views such as the Pyramids, the temples in Luxor and the Nile, Lekegian also inserted hundreds of images drawn from the daily life of peasantry. His subjects were perhaps more multifarious and diverse than of any other photographer working in Egypt at the time. While works of typical, Orientalist ilk are present in his catalogue – images of Nubian women with naked breasts, studio set-ups suggesting a harem like setting and so on – these are balanced with a great quantity of more direct, observational photographs showing daily realities on the streets in both Islamic and European quarters of the country. In addition, Lekegian became a favoured photographer for the Egyptian royalty, many of whom, such as princess Nazli, had their portraits taken by him. After he was employed as the official photographer of Egypt’s British Army, Lekegian’s business truly prospered. This led to numerous comissions to illustrate books and uniquely, provide ‘reportage’ shots on the massive government building operations in the region. These are Lekegian’s least known but perhaps most exceptional works due to their nature as early forms of documentary photography. As of early 1920s Lekegian’s studio mainly concentrated on portraits and producing postcard compilations from his old negatives. It is likely that he shut down the business and retired soon after.

Collectively, Gabriel Lekegian’s oeuvre has a unique place in the annals of 19th and early 20th century Near Eastern photography. As a businessman he was fully aware of the market demands and was willing to satisfy them by producing countless exotic images of the East that ignited the imagination of his predominantly European and American clientele. This led him to participate in a number of international exhibitions as well as the 1893 World’s Columbian exposition in Chicago.[2] The beauty and compositionally superb structure of his photographs attracted the attention of a host of French and British Orientalist painters: Gerome is known to have borrowed these for his slick paintings.[3] Yet, as a photographer who was born and shaped in the Ottoman Empire, his photography also had a progressive side. His photographs of peasants, craftsmen and the poor are not mere theatrical fantasies about a country frozen in past. Instead they show the complex, multifaceted and rapidly changing environment, which Egypt was at the time. He is a rare practitioner of the time who believed that his medium was on par with any other art form and constantly experimented with and developed its aesthetic qualities. The humanism, which marks his works documenting the social conditions of his adopted country, is a characteristic that Lekegian shares with other Armenian photographers working in the region such as Abdullah and Saffarian Freres. Much more research needs to be undertaken in order to fully evaluate the complexity and significance of Lekegian’s fascinating legacy in the light of post-colonial discourses on photography and give it its proper due in the annals of the medium.